Welcome to this topic on the French philosopher Albert Camus! Albert Camus (7 November 1913 – 4 January 1960) was a French philosopher, author, and journalist. His views contributed to the rise of the philosophy known as absurdism. He wrote in his essay The Rebel that his whole life was devoted to opposing the philosophy of nihilism while still delving deeply into individual freedom. He won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1957. Camus did not consider himself to be an existentialist despite usually being classified as a follower of it, even in his lifetime. In a 1945 interview, Camus rejected any ideological associations: “No, I am not an existentialist. Sartre and I are always surprised to see our names linked.”

Welcome to this topic on the French philosopher Albert Camus! Albert Camus (7 November 1913 – 4 January 1960) was a French philosopher, author, and journalist. His views contributed to the rise of the philosophy known as absurdism. He wrote in his essay The Rebel that his whole life was devoted to opposing the philosophy of nihilism while still delving deeply into individual freedom. He won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1957. Camus did not consider himself to be an existentialist despite usually being classified as a follower of it, even in his lifetime. In a 1945 interview, Camus rejected any ideological associations: “No, I am not an existentialist. Sartre and I are always surprised to see our names linked.”

“Man is the only creature who refuses to be what he is.” ~ Albert Camus

Who is Albert Camus?

Albert Camus was born in French Algeria in 1913. His father was killed a year later in World War I, and Camus was brought up by his mother in extreme poverty. He studied philosophy at the University of Algiers, where he suffered the first attack of the tuberculosis which was to recur throughout his life. At the age of 25 he went to live in France, where he became involved in politics. He joined the French Communist Party in 1935 but was expelled in 1937. During World War II he worked for the French Resistance, editing an underground newspaper and writing many of his best-known novels, including The Stranger. He wrote many plays, novels, and essays, and was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1957. Camus died in a car crash aged 46, having discarded a train ticket to accept a lift back to Paris with a friend.

Key philosophical works

- 1942 The Myth of Sisyphus

- 1942 The Stranger

- 1947 The Plague

- 1951 The Rebel

- 1956 The Fall

The Philosophy of Albert Camus

Some people believe that philosophy’s task is to search for the meaning of life. But the French philosopher and novelist Albert Camus thought that philosophy should recognize instead that life is inherently meaningless. While at first this seems a depressing view, Camus believes that only by embracing this idea are we capable of living as fully as possible.

Camus’ idea appears in his essay “The Myth of Sisyphus.” Sisyphus was a Greek king who fell out of favor with the gods, and so was sentenced to a terrible fate in the Underworld. His task was to roll an enormous rock to the top of a hill, only to watch it roll back to the bottom. Sisyphus then had to trudge down the hill to begin the task again, repeating this for all eternity. Camus was fascinated by this myth, because it seemed to him to encapsulate something of the meaninglessness and absurdity of our lives. He sees life as an endless struggle to perform tasks that are essentially meaningless.

Camus’ idea appears in his essay “The Myth of Sisyphus.” Sisyphus was a Greek king who fell out of favor with the gods, and so was sentenced to a terrible fate in the Underworld. His task was to roll an enormous rock to the top of a hill, only to watch it roll back to the bottom. Sisyphus then had to trudge down the hill to begin the task again, repeating this for all eternity. Camus was fascinated by this myth, because it seemed to him to encapsulate something of the meaninglessness and absurdity of our lives. He sees life as an endless struggle to perform tasks that are essentially meaningless.

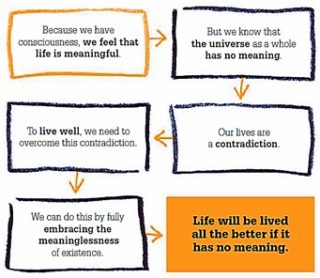

Camus recognizes that much of what we do certainly seems meaningful, but what he is suggesting is quite subtle. On the one hand, we are conscious beings who cannot help living our lives as if they are meaningful. On the other hand, these meanings do not reside out there in the universe; they reside only in our minds. The universe as a whole has no meaning and no purpose; it just is. But because, unlike other living things, we have consciousness, we are the kinds of beings who find meaning and purpose everywhere.

Recognizing the absurd

The absurd, for Camus, is the feeling that we have when we recognize that the meanings we give to life do not exist beyond our own consciousness. It is the result of a contradiction between our own sense of life’s meaning, and our knowledge that nevertheless the universe as a whole, is meaningless.

Camus explores what it might mean to live in the light of this contradiction. He claims that it is only once we can accept the fact that life is meaningless and absurd that we are in a position to live fully. In embracing the absurd, our lives become a constant revolt against the meaninglessness of the universe, and we can live freely.

The Myth of Sisyphus

The central concern of The Myth of Sisyphus is what Camus calls “the absurd.” Camus claims that there is a fundamental conflict between what we want from the universe (whether it be meaning, order, or reasons) and what we find in the universe (formless chaos). We will never find in life itself the meaning that we want to find. Either we will discover that meaning through a leap of faith, by placing our hopes in a God beyond this world, or we will conclude that life is meaningless. Camus opens the essay by asking if this latter conclusion that life is meaningless necessarily leads one to commit suicide. If life has no meaning, does that mean life is not worth living? If that were the case, we would have no option but to make a leap of faith or to commit suicide, says Camus. Camus is interested in pursuing a third possibility: that we can accept and live in a world devoid of meaning or purpose.

The central concern of The Myth of Sisyphus is what Camus calls “the absurd.” Camus claims that there is a fundamental conflict between what we want from the universe (whether it be meaning, order, or reasons) and what we find in the universe (formless chaos). We will never find in life itself the meaning that we want to find. Either we will discover that meaning through a leap of faith, by placing our hopes in a God beyond this world, or we will conclude that life is meaningless. Camus opens the essay by asking if this latter conclusion that life is meaningless necessarily leads one to commit suicide. If life has no meaning, does that mean life is not worth living? If that were the case, we would have no option but to make a leap of faith or to commit suicide, says Camus. Camus is interested in pursuing a third possibility: that we can accept and live in a world devoid of meaning or purpose.

The absurd is a contradiction that cannot be reconciled, and any attempt to reconcile this contradiction is simply an attempt to escape from it: facing the absurd is struggling against it. Camus claims that existentialist philosophers such as Kierkegaard and phenomenologists such as Husserl, all confront the contradiction of the absurd but then try to escape from it. Existentialists find no meaning or order in existence and then attempt to find some sort of transcendence or meaning in this very meaninglessness.

Living with the absurd, Camus suggests, is a matter of facing this fundamental contradiction and maintaining constant awareness of it. Facing the absurd does not entail suicide, but, on the contrary, allows us to live life to its fullest.

Camus identifies three characteristics of the absurd life: revolt (we must not accept any answer or reconciliation in our struggle), freedom (we are absolutely free to think and behave as we choose), and passion (we must pursue a life of rich and diverse experiences).

Camus gives four examples of the absurd life: the seducer, who pursues the passions of the moment; the actor, who compresses the passions of hundreds of lives into a stage career; the conqueror, or rebel, whose political struggle focuses his energies; and the artist, who creates entire worlds. Absurd art does not try to explain experience, but simply describes it. It presents a certain worldview that deals with particular matters rather than aiming for universal themes.

The book ends with a discussion of the myth of Sisyphus, who, according to the Greek myth, was punished for all eternity to roll a rock up a mountain only to have it roll back down to the bottom when he reaches the top. Camus claims that Sisyphus is the ideal absurd hero and that his punishment is representative of the human condition: Sisyphus must struggle perpetually and without hope of success. So long as he accepts that there is nothing more to life than this absurd struggle, then he can find happiness in it, says Camus.

Camus is interested in Sisyphus’ thoughts when marching down the mountain, to start anew. After the stone falls back down the mountain Camus states that “It is during that return, that pause, that Sisyphus interests me. A face that toils so close to stones is already stone itself! I see that man going back down with a heavy yet measured step toward the torment of which he will never know the end.” This is the truly tragic moment, when the hero becomes conscious of his wretched condition. He does not have hope, but “there is no fate that cannot be surmounted by scorn.” Acknowledging the truth will conquer it; Sisyphus, just like the absurd man, keeps pushing. Camus claims that when Sisyphus acknowledges the futility of his task and the certainty of his fate, he is freed to realize the absurdity of his situation and to reach a state of contented acceptance. Camus concludes that “all is well,” indeed, that “one must imagine Sisyphus happy.”

Works Cited

- Stumpf, Samuel Enoch. (2008). From Socrates to Sartre. New York: McGraw Hill Publishing.

- Palmer, Donald. (2006). Looking at Philosophy: The unbearable heaviness of philosophy made ligther, 4th Edition. New York: McGraw Hill Higher Education.

- Ramos, Christine Camela. (2004). Introduction to Philosophy. Manila: Rex Bookstore.

- Gaarder, Jostein. (2004). Sophie’s World. Great Britain: Phoenix House.

- http://www.plato.standford.edu

- http://www.philosophybasic.com