Welcome to our topic on the German philosopher Edmund Husserl. Edmund Husserl is the founder of the philosophical movement called phenomenology. Although he was a big fan of of Rene Descartes, he was one of his staunch critics. His study of phenomenology was a criticism of some Cartesian and rationalist traditions. Now, with this topic, I invite you to come along and together, let us explore the world of phenomenology laid down to us by Edmund Husserl.

Welcome to our topic on the German philosopher Edmund Husserl. Edmund Husserl is the founder of the philosophical movement called phenomenology. Although he was a big fan of of Rene Descartes, he was one of his staunch critics. His study of phenomenology was a criticism of some Cartesian and rationalist traditions. Now, with this topic, I invite you to come along and together, let us explore the world of phenomenology laid down to us by Edmund Husserl.

“Natural objects, for example, must be experienced first before theorizing about them can occur.” ~ Edmund Husserl

Intended learning outcomes

By the time of completion of this topic, you should be able to:

- explain the development of the philosophical ideas of Phenomenology;

- discuss the contributions of Edmund Husserl in the field of philosophy.

Who is Edmund Husserl?

A number of European thinkers had continued to work well within the Continental rationalist philosophical tradition inaugurated by Descartes despite the unrelenting attack on that tradition by the British empiricists and logical positivists. Primary among them was Edmund Husserl (1859–1938), the founder of a philosophy that he called “phenomenology” (from the Greek word phainómenon, meaning “appearance”— hence, Phenomenology is the study of appearances).

He traced the roots of his view to the work of Descartes. Like Descartes, Husserl placed consciousness at the center of all philosophizing, but Husserl had learned from Kant that a theory of consciousness must be as concerned with the form of consciousness as with its content (Descartes had failed to realize this), so he developed a method that would demonstrate both the structure and the content of the mind. This method would be purely descriptive and not theoretical. That is, it would describe the way the world actually reveals itself to consciousness without the aid of any theoretical constructs from either philosophy or science. This method laid bare the world of what Husserl called “the natural standpoint,” which is pretty much the everyday world as experienced unencumbered by the claims of philosophy and science.

Writing about the natural standpoint in his masterpiece, “Ideas: General Introduction to Pure Phenomenology,” Edmund Husserl said:

“I am aware of a world, spread out in space endlessly, and in time becoming and become, without end. I am aware of it, that means, first of all, I discover it immediately, intuitively, I experience it. Through sight, touch, hearing, etc.,… corporeal things… are for me simply there,… present, whether or not I pay them special attention.”

Our World from the Natural Standpoint (Worlds upon Worlds)

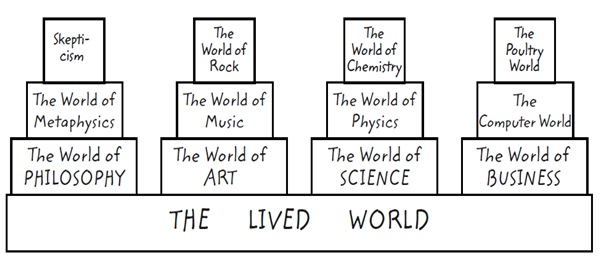

This world of the natural standpoint is the absolute beginning of all philosophy and science. It is the world as actually lived. Other worlds can be built upon the lived world but can never replace it or undermine it. For human beings ultimately there is only the lived world of the natural standpoint. But Husserl wanted to “get behind” the content of the natural standpoint to reveal its structure. To do so, he employed a method like Descartes’ radical doubt, a method that Husserl called “phenomenological reduction” (or epochê, a Greek word meaning “suspension of belief”).

Edmund Husserl and Phenomenological reduction

Phenomenological reduction is a method which brackets any experience whatsoever and describes it while suspending all presuppositions and assumptions normally made about that experience. Bracketing the experience of looking at a coffee cup, for instance, requires suspending the belief that the cup is for holding coffee and that its handle is for grasping. Bracketing reveals the way the cup presents itself to consciousness as a number of possible structures. (I can’t see the front and the back at the same time, nor the top and the bottom, nor see more than one of its possible presentations at any given moment.)

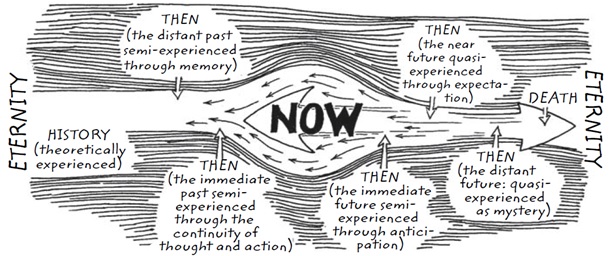

If we apply the epochê to the more philosophically significant example of the experience of time, we must suspend all belief in clocks, train schedules, and calendars. Then we will discover that lived time is always experienced as an eternal now, which is tempered by a memory of earlier nows (the thenness of the past) and is always rushing into the semiexperienceable but ultimately nonexperienceable thenness of the future. Phenomenologically speaking, the time is always “now.” To do anything is to do something now. You can never act then.

Similarly, a phenomenological reduction of the experience of space reveals the difference between lived space and mapped space. Lived space is always experienced in terms of a here-there dichotomy, in which I am always here and everything else is always at different intensities of thereness. (Jean-Paul Sartre, Husserl’s errant disciple, would later draw very pessimistic conclusions from this discovery.) So the here-now experience is the ground zero of the experience of space and time. It is somehow the locus of the self.

One of Husserl’s main insights and one that was to be incorporated into both the later phenomenological tradition and, in some cases, the analytic tradition, was his treatment of the intentionality of all consciousness (i.e., its referentiality). The Husserlian motto here is “All consciousness is consciousness of . . .” (This motto means there is no such thing as self-enclosed thought; one thinks about something.)

“You can’t be just aware—you have to be aware of something, and afraid of something, and concerned about something.” ~ Edmund Husserl

It is this intentionality (or referentiality) that distinguishes consciousness from everything else in the universe. Husserl claimed that the phenomenological suspension could be performed on the object of intentionality (e.g., the coffee cup) or on the act of consciousness itself.

Therefore, he believed it was possible to step back from normal consciousness into a kind of pure consciousness, a transcendental ego, a self-behind-the-self, which, like Descartes’ “I am” (but more deeply real), would be the starting point of all knowledge. Husserl’s ideas get very complex here, and few of his disciples have chosen to follow him into these ethereal regions.

Today, Husserl is most admired for his method. This method has had a number of outstanding adherents, including Martin Heidegger, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, and John Paul Sartre. Shortly, we will review the philosophies of Heidegger and Sartre, Husserl’s best-known, if most wayward, disciples, and we will let them represent the outcome of the evolution of phenomenology into existentialism.

References

- Stumpf, Samuel Enoch. (2008). From Socrates to Sartre. New York: McGraw Hill Publishing.

- Palmer, Donald. (2006). Looking at Philosophy: The unbearable heaviness of philosophy made ligther, 4th Edition. New York: McGraw Hill Higher Education.

- Ramos, Christine Camela. (2004). Introduction to Philosophy. Manila: Rex Bookstore.

- Gaarder, Jostein. (2004). Sophie’s World. Great Britain: Phoenix House.

- http://www.plato.standford.edu

- http://www.philosophybasic.com