Welcome to this topic entitled Georg Hegel! Georg Hegel (1770–1831) belongs to the period of German idealism in the decades following Immanuel Kant. The most systematic of the post-Kantian idealists, Georg Hegel attempted, throughout his published writings as well as in his lectures, to elaborate a comprehensive and systematic philosophy from a purportedly logical starting point. He is perhaps most well-known for his teleological account of history as an evolution of ideas in his Absolute Idealism or dialectic idealism philosophy.

Welcome to this topic entitled Georg Hegel! Georg Hegel (1770–1831) belongs to the period of German idealism in the decades following Immanuel Kant. The most systematic of the post-Kantian idealists, Georg Hegel attempted, throughout his published writings as well as in his lectures, to elaborate a comprehensive and systematic philosophy from a purportedly logical starting point. He is perhaps most well-known for his teleological account of history as an evolution of ideas in his Absolute Idealism or dialectic idealism philosophy.

“The history of the world is none other than the progress of the consciousness of freedom.” ~Georg Hegel

Who is Georg Hegel?

Georg Hegel was born in 1770 in Stuttgart, Germany, and studied theology at Tübingen where he met and became friends with the poet Friedrich Hölderlin and the philosopher Friedrich Schelling. He spent several years working as a tutor before an inheritance allowed him to join Schelling at the University of Jena. Hegel was forced to leave Jena when Napoleon’s troops occupied the town, and just managed to rescue his major work, Phenomenology of Spirit, which catapulted him to a dominant position in German philosophy. In need of funds, he became a newspaper editor and then a school headmaster before being appointed to the chair of philosophy first in Heidelberg and then at the prestigious University of Berlin. At the age of 41 he married Marie von Tucher, with whom he had three children. Hegel died in 1831 during a cholera epidemic.

Key philosophical works

- 1807 Phenomenology of Spirit

- 1812–16 Science of Logic

- 1817 Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences

The philosophy of Georg Hegel

Hegel was the single most famous philosopher in Germany during the first half of the 19th century. His central idea was that all phenomena, from consciousness to political institutions, are aspects of a single Spirit (by which he means “mind” or “idea”) that over the course of time is reintegrating these aspects into itself. This process of reintegration is what Hegel calls the “dialectic”, and it is one that we (who are all aspects of Spirit) understand as “history.” Hegel is therefore a monist, for he believes that all things are aspects of a single thing, and an idealist, for he believes that reality is ultimately something that is not material (in this case Spirit). Hegel’s idea radically altered the philosophical landscape, and to fully grasp its implications we need to take a look at the background to his thought.

History and consciousness

Few philosophers would deny that human beings are, to a great extent, historical—that we inherit things from the past, change them, and then pass them on to future generations. Language, for example, is something that we learn and change as we use it, and the same is true of science—scientists start with a body of theory, and then go on either to confirm or to disconfirm it. The same is also true of social institutions, such as the family, the state, banks, churches, and so on—most of which are modified forms of earlier practices or institutions.

Human beings, therefore, never begin their existence from scratch, but always within some kind of context—a context that changes, sometimes radically within a single generation. Some things, however, do not immediately appear to be historical, or subject to change. An example of such a thing is consciousness. We know for certain that what we are conscious of will change, but what it means to be conscious—what kind of a thing it is to be awake, to be aware, to be capable of thinking and making decisions—is something that we tend to believe has always been the same for everyone. Likewise, it seems plausible to claim that the structures of thought are not historical—that the kind of activity that thinking is, and what mental faculties it relies on (memory, perception, understanding, and so on), has always been the same for everyone throughout history. This was certainly what Hegel’s great idealist predecessor, Immanuel Kant, believed—and to understand Hegel, we need to know what he thought about Kant’s work.

Human beings, therefore, never begin their existence from scratch, but always within some kind of context—a context that changes, sometimes radically within a single generation. Some things, however, do not immediately appear to be historical, or subject to change. An example of such a thing is consciousness. We know for certain that what we are conscious of will change, but what it means to be conscious—what kind of a thing it is to be awake, to be aware, to be capable of thinking and making decisions—is something that we tend to believe has always been the same for everyone. Likewise, it seems plausible to claim that the structures of thought are not historical—that the kind of activity that thinking is, and what mental faculties it relies on (memory, perception, understanding, and so on), has always been the same for everyone throughout history. This was certainly what Hegel’s great idealist predecessor, Immanuel Kant, believed—and to understand Hegel, we need to know what he thought about Kant’s work.

Hegel’s Dialectic

The notion of dialectic is central to what Hegel calls his immanent (internal) account of the development of things. He declares that his account will guarantee four things.

- First, that no assumptions are made.

- Second, that only the broadest notions possible are employed, the better to avoid asserting anything without justification.

- Third, that it shows how a general notion gives rise to other, more specific, notions.

- Fourth, that this process happens entirely from “within” the notion itself.

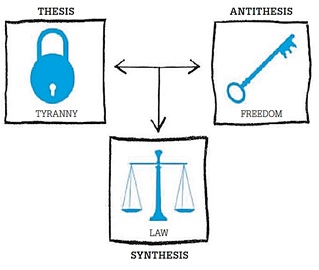

This fourth requirement reveals the core of Hegel’s logic—namely that every notion, or “thesis”, contains within itself a contradiction, or “antithesis”, which is only resolved by the emergence of a newer, richer notion, called a “synthesis”, from the original notion itself. One consequence of this immanent process is that when we become aware of the synthesis, we realize that what we saw as the earlier contradiction in the thesis was only an apparent contradiction, one that was caused by some limitation in our understanding of the original notion.

An example of this logical progression appears at the beginning of Hegel’s Science of Logic, where he introduces the most general and all-inclusive notion of “pure being”—meaning anything that in any sense could be said to be. He then shows that this concept contains a contradiction—namely, that it requires the opposite concept of “nothingness” or “notbeing” for it to be fully understood. Hegel then shows that this contradiction is simply a conflict between two aspects of a single, higher concept in which they find resolution. In the case of “being” and “not-being”, the concept that resolves them is “becoming.”

When we say that something “becomes”, we mean that it moves from a state of not-being to a state of being—so it turns out that the concept of “being” that we started off with was not really a single concept at all, but merely one aspect of the three-part notion of “becoming.”

The vital point here is that the concept of becoming” is not introduced from “outside”, as it were, to resolve the contradiction between “being” and “not-being.” On the contrary, Hegel’s analysis shows that “becoming” was always the meaning of “being” and “notbeing”, and that all we had to do was analyze these concepts to see their underlying logic. This resolution of a thesis (being) with its antithesis (not-being) in a synthesis (becoming) is just the beginning of the dialectical process, which goes on to repeat itself at a higher level. That is, any new synthesis turns out, on further analysis, to involve its own contradiction, and this in turn is overcome by a still richer or “higher” notion. All ideas, according to Hegel, are interconnected in this way, and the process of revealing those connections is what Hegel calls his “dialectical method.”

The vital point here is that the concept of becoming” is not introduced from “outside”, as it were, to resolve the contradiction between “being” and “not-being.” On the contrary, Hegel’s analysis shows that “becoming” was always the meaning of “being” and “notbeing”, and that all we had to do was analyze these concepts to see their underlying logic. This resolution of a thesis (being) with its antithesis (not-being) in a synthesis (becoming) is just the beginning of the dialectical process, which goes on to repeat itself at a higher level. That is, any new synthesis turns out, on further analysis, to involve its own contradiction, and this in turn is overcome by a still richer or “higher” notion. All ideas, according to Hegel, are interconnected in this way, and the process of revealing those connections is what Hegel calls his “dialectical method.”

Dialectic and the world

The discussion of Hegel’s dialectic above uses terms such as “emerge”, “development”, and “movement.” On the one hand, these terms reflect something important about this method of philosophy—that it starts without assumptions and from the least controversial point, and allows ever richer and truer concepts to reveal themselves through the process of dialectical unfolding. On the other hand, however, Hegel clearly argues that these developments are not simply interesting facts of logic, but are real developments that can be seen at work in history. For example, a man from ancient Greece and a man living in the modern world will obviously think about different things, but Hegel claims that their very ways of thinking are different, and represent different kinds of consciousness—or different stages in the historical development of thought and consciousness.

Hegel’s first major work, Phenomenology of Spirit, gives an account of the dialectical development of these forms of consciousness. He starts with the types of consciousness that an individual human being might possess, and works up to collective forms of consciousness. He does so in such a way as to show that these types of consciousness are to be found externalized in particular historical periods or events—most famously, for example, in the American and French revolutions.

Indeed, Hegel even argues that at certain times in history, Spirit’s next revolutionary change may manifest itself as an individual such as Napoleon Bonaparte, according to Hegel, perfectly embodied the zeitgeist (spirit of the age) and was able, through his actions, to move history into the next stage of its development. Napoleon, who, as an individual consciousness, is completely unaware of his or her role in the history of Spirit. And the progress that these individuals make is always characterized by the freeing of aspects of Spirit (in human form) from recurring states of oppression —of overcoming tyrannies that may themselves be the result of the overcoming of previous tyrannies.

This extraordinary idea—that the nature of consciousness has changed through time, and changed in accordance with a pattern that is visible in history—means that there is nothing about human beings that is not historical in character. Moreover, this historical development of consciousness cannot simply have happened at random. Since it is a dialectical process, it must in some sense contain both a particular sense of direction and an end point. Hegel calls this end point “Absolute Spirit”—and by this he means a future stage of consciousness which no longer even belongs to individuals, but which instead belongs to reality as a whole.

The “Whole of Spirit”, or “Absolute Spirit”, is the end point of Hegel’s dialectic. However, the preceding stages are not left behind, as it were, but are revealed as insufficiently analyzed aspects of Spirit as a whole. Indeed, what we think of as an individual person is not a separate constituent of reality, but is an aspect of how Spirit develops—or how it “empties itself out into time.” Thus, Hegel writes,

“The True is the Whole. But the Whole is nothing other than the essence consummating itself through its development.”

Reality is Spirit—both thought and what is known by thought—and undergoes a process of historical development.

References

- Dorling Kindersley. (2011). The Philosophy Book. New York: DK Publishing.

- Stumpf, Samuel Enoch. (2008). From Socrates to Sartre and Beyond. New York: McGraw Hill Publishing.

- Palmer, Donald.(2006). Looking at philosophy:The unbearable heaviness of philosophy made lighter 4th Edition. New York: McGraw Hill Companies.

- Gaarder, Jostein. (2004). Sophie’s World. Great Britain: Phoenix House.

- Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Accessed on September 19, 2017 at https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/hegel/

- Georg Hegel. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Accessed on September 19, 2017 at http://www.iep.utm.edu/sartre-ex/

- http://www.plato.standford.edu

- Georg Hegel: The Basics of Philosophy. Accessed on September 17, 2017 at www.philosophybasics.com