Welcome to this topic entitled Medieval philosophy! Medieval ages covers a period of “Dark Ages” in Europe due to the rampaging barbarians who ransacked the crumbling Roman Empire. Medieval philosophy emphasizes the influence of Christianity and many of the philosophers of the period were greatly concerned with proving the existence of God and reconciling Christianity with classical philosophy. An important development in the Medieval period was the establishment of the first universities with professional full-time scholars. It should also be noted that there was also a strong resurgence in Islamic and Jewish philosophy at this time. The flowering of Islamic empire with the accompanying Islamic philosophy of Avicenna (Ibn Sinna) and Averroes (Ibn Rushd). As a philosopher and a devout Muslim, Avicenna tried to reconcile the rational philosophy of Aristotelianism and Neo-Platonism with Islamic theology (Avicennism). Averroes is perhaps most famous for his translations and detailed commentaries on the works of Aristotle, which earned for him the title of the “The Commentator.” In the Islamic world, he played a decisive role in the defence of Greek philosophy (Averroeism).

On the other side, Jewish philosophy of Maimonides made a dramatic presence too. Maimonides composed works of Jewish scholarship, rabbinic law, philosophy and medical texts, mainly in Arabic. In philosophy, Maimonides was a Jewish Scholastic and he exerted an important influence on the later medieval Scholastics such as St. Thomas Aquinas. His aim was to reconcile Aristotelian philosophy and science with the teachings of the Jewish Torah. Now, as peace started to reign during the late Medieval ages so does Medieval philosophy started to flourish. In this topic we will highlight two outstanding philosophers namely; St. Augustine of Hippo and St. Thomas of Aquinas.

Intended learning outcomes (ILOs)

At the end of this topic, you should be able to:

- Explain the dynamics between faith and reason as discussed by St. Augustine and St. Thomas, and

- Discuss the philosophical proofs of God’s Existence.

Medieval philosophers

Who is St. Augustine?

Aurelius Augustinus of Hippo (A.D. 354 – 430) was an Algerian-Roman philosopher and theologian of the late Roman / early Medieval period. He is one of the most important early figures in the development of Western Christianity, and was a major figure in bringing Christianity to dominance in the previously pagan Roman Empire. He is often considered the father of orthodox theology and the greatest of the four great fathers of the Latin Church (along with St. Ambrose, St. Jerome and St. Gregory). Augustine developed a philosophical and theological system which employed elements of Plato and Neo-Platonism in support of Christian orthodoxy. His many works profoundly influenced the medieval worldview.

Aurelius Augustinus of Hippo (A.D. 354 – 430) was an Algerian-Roman philosopher and theologian of the late Roman / early Medieval period. He is one of the most important early figures in the development of Western Christianity, and was a major figure in bringing Christianity to dominance in the previously pagan Roman Empire. He is often considered the father of orthodox theology and the greatest of the four great fathers of the Latin Church (along with St. Ambrose, St. Jerome and St. Gregory). Augustine developed a philosophical and theological system which employed elements of Plato and Neo-Platonism in support of Christian orthodoxy. His many works profoundly influenced the medieval worldview.

His father Patricius was a pagan, but his mother Monica was a devout Catholic (and is herself revered as a Christian saint), so he was raised as a Catholic. He was educated in the finest schools at that time but he was exposed to the pagan (Roman) beliefs and philosophy. At age 17, he went to Carthage, to continue his education in rhetoric, and there he came under the influence of the controversial Persian religious cult of Manichaeism. The Manicheans see good and evil as dual forces that rule the universe. If we commit evil acts, the devil temporarily won. He lived a hedonistic lifestyle for a time, including frequent visits to the brothels of Carthage, and developed a relationship with a young woman named Floria Aemilia, who would be his concubine for over fifteen years, and who bore him a son, Adeodatus.

During his time at Rome and Milan, he had moved away from Manichaeism, initially embracing Skepticism. A combination of his own studies in Neo-Platonism, his reading of an account of the life of Saint Anthony of the Desert, and the combined influence of his mother, his friend Simplicianus and, particularly, the influential bishop of Milan, Saint Ambrose (338 – 397), gradually inclined Augustine towards Christianity. In the summer of 386, he officially converted to Catholic Christianity, abandoned his career in rhetoric, quit his teaching position in Milan, and gave up any ideas of the society marriage which had been arranged for him, and devoted himself entirely to serving God, the priesthood and celibacy. He detailed this spiritual journey in his famous “Confessions”, which became a classic of both Christian theology and world literature.

St. Augustine’s works

Augustine wrote over 100 works in Latin, many of them texts on Christian doctrine. His masterpieces include:

- “Confessiones” or “Confessions” in English which is a personal account of his early life, completed in about 397 highlighting his sinful ways of life as a youth.

- “De civitate Dei” or “The City of God” consisting of 22 books started in 413 and finished in 426, dealing with God, martyrdom, Jews and other Christian philosophies, and

- “De Trinitate” or “On the Trinity“, consisting of 15 books written over the final 30 years of his life, in which he developed the “psychological analogy” of the Trinity.

He was fascinated by Plato’s works and learned much about him. In essence, he Christianized Plato’s ideas because his entire philosophy is built entirely on Plato’s World of Forms. In “The City of God“, he conceived of the church as a heavenly city or kingdom, ruled by love, which will ultimately triumph over all earthly empires which are self-indulgent and ruled by pride.

The problem of good and evil

Augustine formulated a series of arguments which tackles the medieval concern of the existence of good and evil. These are

- If God is entirely good and all-powerful, why is there evil in the world?

- He believes that although God created everything that exists, he did not create evil, because evil is not a thing, but a lack or deficiency of something.

- For example, the evil suffered by a blind man is that he is without sight; the evil in a thief is that he lacks honesty.

- Why God should have created the world in such a way as to allow there to be these natural and moral evils, or deficiencies?

- His answer revolves around the idea that humans are rational beings.

- He argues that in order for God to create rational creatures, such as human beings, he had to give them freedom of will.

- Having freedom of will means being able to choose, including choosing between good and evil.

- If God is all-wise (omniscient), then he knows the future. If he knows the future, then the future must unfold exactly in accordance with his knowledge (otherwise, he does not know the future). If the events in the future must occur according to God’s foreknowledge of them, then they are necessary. If they are necessary, then there is no freedom. If there is no freedom, then humans are not responsible for their acts, in which case, it would be immoral to punish people for their sins.

- For God, there is no past or future, only an eternal present. For him, everything exists in an eternal moment.

- To say “God knew millions of years before Judas’s birth that he would betray Jesus” is to make the human error of believing that God is in time. In fact, God is outside of time. (That’s what it means to say that God is eternal.)

- Another tack of Augustine’s is to admit that God’s knowledge of the world entails necessity, but to deny that necessity is incompatible with freedom.

- Augustine believed that freedom is the capacity to do what one wants, and one can do what one wants even if God (or anyone else) already knows what that person wants.

- Augustine pointed out that God’s foreknowledge of a decision doesn’t cause the decision, any more than my own acts are caused by my knowledge of what I’m going to do.

Who is St. Thomas?

St. Thomas Aquinas (a.k.a.Thomas of Aquin or Aquino) (c. 1225 – 1274) was an Italian philosopher and theologian and a giant of Medieval philosophy. His father was Count Landulph and his mother was Theodora, Countess of Theate. At the age of 5, Aquinas began his early education at a monastery, and at the age of 16 he continued his studies at the University of Naples. Thomas began to veer towards the Dominican Order, much to the objections of the father. However, after the intervention of Pope Innocent IV, he became a Dominican monk in 1242. In 1244, the promising young Aquinas was sent to study under Albertus Magnus in the University of Cologne and then in Paris, where he distinguished himself in arguments. Having graduated as a bachelor of theology in 1248, he returned to Cologne as second lecturer and magister studentium and began his literary activity and public life.

In 1324, fifty years after Thomas Aquinas’ death, Pope John XXII in Avignon pronounced him a saint of the Catholic church, and his theology began its rise to prestige. In 1568, he was named a Doctor of the Church. In 1879, Pope Leo XIII stated that Aquinas’ theology was a definitive exposition of Catholic doctrine, and directed clergy to take the teachings of Aquinas as the basis of their theological positions. Today, he is considered by many Catholics to be the Catholic church’s greatest theologian and philosopher.

St. Thomas’ Works

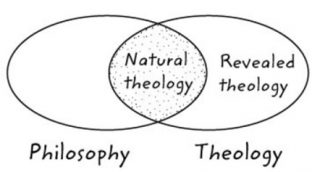

St. Thomas believed that truth becomes known through both natural revelation (certain truths are available to all people through their human nature and through correct human reasoning) and supernatural revelation (faith-based knowledge revealed through scripture), and he was careful to separate these two elements, which he saw as complementary rather than contradictory in nature. Thus, although one may deduce the existence of God and His attributes through reason, certain specifics (such as the Trinity and the Incarnation) may be known only through special revelation and may not otherwise be deduced.

St. Thomas’ great works are:

- Summa Contra Gentiles often published in English under the title “On the Truth of the Catholic Faith”, written between 1258 and 1264, which is a broadly-based philosophical work directed at non-Christians, and

- Summa Theologica translated as “Compendium of Theology“, written between 1265 and 1274. This is addressed largely to Christians and is more a work of Christian theology.

Faith and reason

Concerning the problem of reason versus faith, Thomas began by distinguishing between philosophy and theology. The philosopher uses human reason alone. The theologian accepts revelation as authority. Then Thomas distinguished between revealed theology (accepted purely on faith) and natural theology (susceptible of the proof of reason). That is, he showed where philosophy and theology overlap. Thomas admitted that sometimes reason cannot establish the claims of faith, and he left those claims to the theologians (e.g., the claim that the universe has a beginning in time). Faith and reason are the two primary tools which are both necessary together for processing this data in order to obtain true knowledge of God. He believed that God reveals himself through nature, so that rational thinking and the study of nature is also the study of God. This is clearly a blend of Aristotelian Greek philosophy with Christian doctrine. St. Thomas, in essence, Christianized the ideas of Aristotle.

Concerning the problem of reason versus faith, Thomas began by distinguishing between philosophy and theology. The philosopher uses human reason alone. The theologian accepts revelation as authority. Then Thomas distinguished between revealed theology (accepted purely on faith) and natural theology (susceptible of the proof of reason). That is, he showed where philosophy and theology overlap. Thomas admitted that sometimes reason cannot establish the claims of faith, and he left those claims to the theologians (e.g., the claim that the universe has a beginning in time). Faith and reason are the two primary tools which are both necessary together for processing this data in order to obtain true knowledge of God. He believed that God reveals himself through nature, so that rational thinking and the study of nature is also the study of God. This is clearly a blend of Aristotelian Greek philosophy with Christian doctrine. St. Thomas, in essence, Christianized the ideas of Aristotle.

Essence and existence

Thomas stressed even more than did Aristotle the idea of actuality, which he called “act” (actus in Latin), and associated it strongly with the idea of “being” (esse in Latin). Esse is the actus whereby an essence or a form (what a thing is) has its being. He argued:

“There is no essence without existence and no existence without essence.”

In other words, chimeras and griffins do not have essences because they do not have being. They do not exist and never have existed. They are just fanciful constructions based on imaginative abstraction. What something is (its essence) is not the same as that it is (its existence); otherwise, it would always exist, which is contrary to fact.

In other words, chimeras and griffins do not have essences because they do not have being. They do not exist and never have existed. They are just fanciful constructions based on imaginative abstraction. What something is (its essence) is not the same as that it is (its existence); otherwise, it would always exist, which is contrary to fact.

Further, if existing were identical with any one kind of thing, everything existing would be only that one kind—again, contrary to fact. Aquinas made a unique contribution to metaphysics by highlighting that existence is the most important actuality in anything, without which even form (essence) cannot be actual.

Proof of God’s Existence

From his consideration of what God is not, Aquinas proposed five positive statements about the divine qualities or the nature of God:

- God is simple, without composition of parts, such as body and soul, or matter and form.

- God is perfect, lacking nothing.

- God is infinite, and not limited in the ways that created beings are physically, intellectually, and emotionally limited.

- God is immutable, incapable of change in respect of essence and character.

- God is one, such that God’s essence is the same as God’s existence.

Five Philosophical Proofs of God’s Existence

Aquinas believed that the existence of God is neither self-evident nor beyond proof. In the “Summa Theologica”, he details five rational proofs for the existence of God, the “Quinquae Viae” (or the “Five Ways”), some of which are really re-statements of each other:

- The Argument of the Unmoved Mover (ex motu). Everything that is moved is moved by a mover, therefore there is an unmoved mover from whom all motion proceeds, which is God.

- St. Thomas Aquinas, studying the works of the Greek philosopher Aristotle, concluded from common observation that an object that is in motion (e.g. the planets, a rolling stone) is put in motion by some other object or force.

- From this, Aquinas believes that ultimately there must have been an UNMOVED MOVER (GOD) who first put things in motion. Follow the argument this way:

- Nothing can move itself.

- If every object in motion had a mover, then the first object in motion needed a mover.

- Movement cannot go on for infinity.This first mover is the Unmoved Mover, called God.

- Aquinas is starting from an a posteriori position.

- For Aquinas motion includes any kind of change e.g. growth.

- Aquinas argues that the natural condition is for things to be at rest.

- Something which is moving is therefore unnatural and must have been put into that state by some external supernatural power which is God.

- The Argument of the First Cause (ex causa). Everything that is caused is caused by something else, therefore there must be an uncaused cause of all caused things, which is God.

- This Way deals with the issue of existence. Aquinas concluded that common sense observation tells us that no object creates itself.

- In other words, some previous object had to create it.

- Aquinas believed that ultimately there must have been an UNCAUSED FIRST CAUSE (GOD) who began the chain of existence for all things.

- Follow the argument this way:

- There exists things that are caused (created) by other things.

- Nothing can be the cause of itself (nothing can create itself).

- There cannot be an endless string of objects causing other objects to exist.

- Therefore, there must be an uncaused first cause called God.

- The Argument from Contingency (ex contingentia). There are contingent beings in the universe which may either exist or not exist and, as it is impossible for everything in the universe to be contingent (as something cannot come of nothing), so there must be a necessary being whose existence is not contingent on any other being, which is God.

- This Way is sometimes referred to as the modal cosmological argument.

- Modal is a reference to contingency and necessary.

- This Way defines two types of objects in the universe: Contingent beings and Necessary beings. A contingent being is an object that cannot exist without a necessary being causing its existence.

- Aquinas believed that the existence of contingent beings would ultimately necessitate a being which must exist for all of the contingent beings to exist.

- This being, called a necessary being, is what we call God. Follow the argument this way:

- Contingent beings are caused.

- Not every being can be contingent.

- There must exist a being which is necessary to cause contingent beings.

- This necessary being is God.

- The Argument from Degree (ex gradu). There are various degrees of perfection which may be found throughout the universe, so there must be a pinnacle of perfection from which lesser degrees of perfection derive, which is God.

- St. Thomas formulated this Way from a very interesting observation about the qualities of things.

- For example one may say that of two marble sculptures one is more beautiful than the other.

- So for these two objects, one has a greater degree of beauty than the next.

- St. Thomas formulated this Way from a very interesting observation about the qualities of things.

- For example one may say that of two marble sculptures one is more beautiful than the other.

- So for these two objects, one has a greater degree of beauty than the next.

- The Argument from Intelligent Design (ex fine). All natural bodies in the world (which are in themselves unintelligent) act towards ends (which is characteristic of intelligence), therefore there must be an intelligent being that guides all natural bodies towards their ends, which is God.

- The final Way that St. Thomas Aquinas speaks of has to do with the observable universe and the order of nature.

- Aquinas states that common sense tells us that the universe works in such a way, that one can conclude that is was designed by an intelligent designer, God.

- In other words, all physical laws and the order of nature and life were designed and ordered by God, the intelligent designer.

Works cited

- Stumpf, S. (2008). Socrates to Sartre: A History of Philosophy. New York: McGraw Hill Higher Education.

- Gaarder, Jostein.(2004). Sophie’s World. Great Britain: Phoenix House.

- Palmer, Donald. (2006). Looking at Philosophy: The unbearable heaviness of philosophy made ligther, 4th Edition. New York: McGraw Hill Higher Education.

- http://www.plato.standford.edu

- http://www.philosophybasic.com

- Medieval university image courtesy of wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/fc/Laurentius_de_Voltolina_001.jpg