Welcome to this post entitled Wilhelm Leibniz! Wilhelm Leibniz is a many-splendored genius of his time. He is a German philosopher in the wagon of continental rationalism. As another rationalism stalwart, he advocated the use of reason as the true source of knowledge. Wilhelm Leibniz was a rationalist, and his distinction between truths of reasoning and truths of fact marks an interesting twist in the debate between rationalism and empiricism. His claim, which he makes in most famous work, the Monadology, is that in principle, all knowledge can be accessed by rational reflection. So, hang in there and together, let us fathom the depth and width of Leibniz’s mind and try to dig deeper into his monads and avoid not to lose our sanity. Enjoy!

“There are two kinds of truths – truths of reasoning and truths of facts.” ~ Wilhelm Gottfried von Leibniz

Intended learning outcomes

By the completion of this topic, you should be able to:

- Explain the influence of the monads ideas of Leibniz and his contributions to the modern philosophy of metaphysics and epistemology.

Who is Wilhelm Leibniz?

Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716) was a person of unusually wide genius, even for a great philosopher. He invented calculus independently of Newton, and published it before Newton did, although Newton had invented it earlier. It is Leibniz’s notation, not Newton’s that mathematicians now use. He invented the concept of kinetic energy. He invented mathematical or symbolic logic, although he did not publish his invention: if he had done so the subject would have got going one and a half centuries before it did. He was a universal genius who created a plan for the invasion of Egypt that may have been used by Napoleon 120 years later. Leibniz also invented a calculating machine that could add, subtract, and do square roots. And then, in addition to being one of the greatest mathematicians of all time, he was one of the most influential of philosophers.

Like Spinoza, Wilhelm Leibniz wished to correct the errors of Cartesian metaphysics without rejecting its main structure, but Leibniz was not satisfied with Spinoza’s pantheistic monism nor with his naturalism (i.e., his view that all is nature and that the human being has no special status in reality). Leibniz wanted a return to a Cartesian system with real individuals and a transcendent God.

Leibniz’s system, as set forth in his books Monadology and Essays in Theodicy, can be summarized in terms of three principles:

- The principle of identity,

- The principle of sufficient reason, and

- The principle of internal harmony.

Principle of Identity

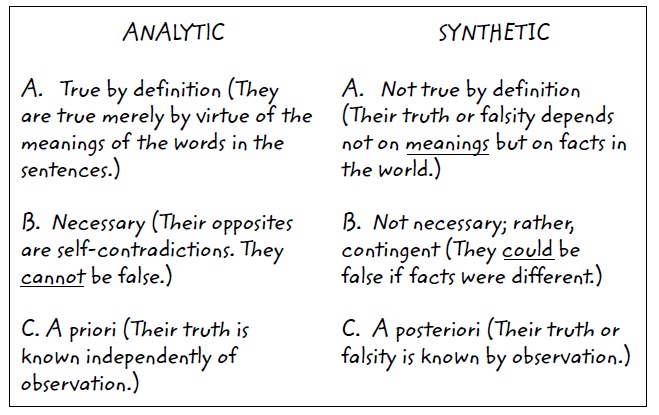

In his principle of identity, Wilhelm Leibniz divided all propositions into two types, which later philosophers would call analytic propositions and synthetic propositions. Take a look at the following table:

The following are some examples of Analytic propositions:

- All bachelors are men.

- 2 + 3 = 5.

- Either A or not -A.

This category includes definitions and parts of definitions (example 1) and arithmetic and the principles of logic (examples 2 and 3). Analytic propositions were said by Leibniz to be based on the principle of identity in the sense that this principle is the positive counterpart of the Principle of Noncontradiction (which says that it cannot be the case that A and not–A at the same time) in that the

negation of every analytic sentence is a self-contradiction (e.g., “Not all bachelors are men” implies the contradictory assertion “Some men are not men” because the definition of “bachelor” is “unmarried man.”

The following are some examples of Synthetic propositions:

- The cat is on the mat.

- Caesar crossed the Rubicon on 49 B.C.

Now, having drawn what many philosophers believe to be a very important distinction, Wilhelm Leibniz made the surprising move of claiming that all synthetic sentences are really analytic. Sub specie aeternitatis; that is to say, from God’s point of view, it is the case that all true sentences are necessarily true, even though it doesn’t seem to be the case to us humans.For Leibniz, Tuffy the cat’s characteristic of “being on the mat at time T” is a characteristic necessary to that specific cat in the same way that “being a feline” is necessary to it.

The Principle of Sufficient Reason

This line of reasoning brings us to the principle of sufficient reason. According to Leibniz, for anything that exists, there is some reason why it exists and why it exists exactly as it does exist. Leibniz claimed that this second principle is the main principle of rationality and that anyone who rejects this principle is irrational. If the cat is on the mat, then there must be some reason why the cat exists at all, and why it is on the mat and not, for example, in the dishwasher. Both these reasons should be open to human scientific inquiry, though perhaps only God can know why the cat exists necessarily and is necessarily on the mat.

What is true of the cat is true of the whole cosmos, said Leibniz. There must be a reason why the universe exists at all, and this reason ought to be open to rational human inquiry. The deepest question, according to Leibniz, is “why there exists something rather than nothing.” Like Saint Thomas, he concluded that the only possible answer would be in terms of an uncaused cause, an all-perfect God whose being was itself necessary. So if Leibniz was right, we can derive the proof of the existence of God from the bare notion of rationality plus the self-evident proposition that something rather than nothing exists.

The Principle of Internal Harmony

This conclusion leads us to the principle of internal harmony. If there is a God, God must be both rational and good. Such a divinity, Leibniz told us, must desire and be capable of creating the maximum amount of existence possible (“metaphysical perfection”) and the maximum amount of activity possible (“moral perfection”). Therefore, at the moment of creation, God entertained all possibilities. He actualized only those possibilities that would guarantee the maximum amount of metaphysical and moral perfection.

For example, God did not just consider the individual “Caesar” in all of Caesar’s ramifications (would write The Gallic Wars, would cross the Rubicon in 49 B.C.E., would die on the Ides of March) before actualizing him. Perhaps God considered actualizing (i.e., creating) in Caesar’s place “Gaesar” and “Creasar,” who, as potential actualizations, were identical to Caesar in all respects except that Gaesar would cross not the Rubicon but the Delaware River in 49 B.C.E., and Creasar would cross the Love Canal.

God saw that only Caesar was compatible with the rest of the possibilities that he would activate, and therefore he actualized him and not the others. A similar thought experiment could be performed with God’s creation of Brutus (as opposed, perhaps, to “Brautus” and “Brutos”). So the relation between Caesar and Brutus is not a causal one but one of internal harmony. And the same holds true of the relations among all substances. God activates only substances that will necessarily harmonize with each other to the greatest extent possible. This principle now explains why all true sentences are analytic. If Tuffy is on the mat at 8 P.M., that is because this cat must be on the mat at 8 P.M. (otherwise it is not Tuffy, but another cat). It also explains Leibniz’s notorious claim that this is the best of all possible worlds and you are the best of all possible you’s. His actual words are “Hence the world is not only the most admirable machine, but in so far as it consists of minds, it is also the best Republic, that in which the minds are granted the greatest possible happiness and joy.” The world may appear very imperfect to you, but if you knew what the alternative was, you would be very grateful indeed to God.

A universe in our minds

Wilhelm Leibniz holds that every part of the world, every individual thing, has a distinct concept or “notion” associated with it, and that every such notion contains within it everything that is true about itself, including its relations to other things. Because everything in the universe is connected, he argues, it follows that every notion is connected to every other notion, and so it is possible—at least in principle—to follow these connections and to discover truths about the entire universe through rational reflection alone. Such reflection leads to Leibniz’s “truths of reasoning.” However, the human mind can grasp only a small number of such truths (such as those of mathematics), and so it has to rely on experience, which yields “truths of fact.”

So how is it possible to progress from knowing that it is snowing, for example, to knowing what will happen tomorrow somewhere on the other side of the world? For Leibniz, the answer lies in the fact that the universe is composed of individual, simple substances called “monads.” Each monad is isolated from other monads, and each contains a complete representation of the whole universe in its past, present, and future states. This representation is synchronized between all the monads, so that each one has the same content. According to Leibniz, this is how God created things—in a state of “pre-established harmony.”

Leibniz claims that every human mind is a monad, and so contains a complete representation of the universe. It is therefore possible in principle for us to learn everything that there is to know about our world and beyond simply by exploring our own minds.

Leibniz’s legacy

In spite of the difficulties inherent in Leibniz’s theory, his ideas went on to shape the work of numerous philosophers, including David Hume and Immanuel Kant. Kant refined Leibniz’s truths of reasoning and

truths of fact into the distinction between “analytic” and “synthetic” statements—a division that has remained central to European philosophy ever since.

References

- Dorling Kindersley. (2011). The Philosophy Book. New York: DK Publishing.

- Stumpf, Samuel Enoch. (2008). From Socrates to Sartre and Beyond. New York: McGraw Hill Publishing.

- Palmer, Donald.(2006). Looking at philosophy:The unbearable heaviness of philosophy made lighter 4th Edition. New York: McGraw Hill Companies.

- Ramos, Christine Camela. (2004). Introduction to Philosophy. Manila: Rex Bookstore.Gaarder, Jostein. (2004). Sophie’s World. Great Britain: Phoenix House.

- http://www.plato.standford.edu