Welcome my dear Young Philosophers! Our topic for today is none other than Aristotle. Aristotle is one of the most important founding figures in Western Philosophy, and together with his teacher Plato, the first to create a comprehensive system of philosophy, encompassing Ethics, Aesthetics, Politics, Metaphysics, Logic and the sciences. Aristotle forms the triad of great Athenian philosophers which include Socrates, Plato and him. Simply put, his contributions to many fields of endeavor cemented his legacy which endures even today. So, join me as we celebrate the achievement of the man and his philosophy. Enjoy learning!

Welcome my dear Young Philosophers! Our topic for today is none other than Aristotle. Aristotle is one of the most important founding figures in Western Philosophy, and together with his teacher Plato, the first to create a comprehensive system of philosophy, encompassing Ethics, Aesthetics, Politics, Metaphysics, Logic and the sciences. Aristotle forms the triad of great Athenian philosophers which include Socrates, Plato and him. Simply put, his contributions to many fields of endeavor cemented his legacy which endures even today. So, join me as we celebrate the achievement of the man and his philosophy. Enjoy learning!

“Truth resides in the world around us.” ~ Aristotle

Intended learning outcomes

At the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- Identify the ideas on human person according to Aristotle;

- Discuss the Aristotelian Concept of Happiness, Virtue and Golden Mean.

Who is Aristotle?

Aristotle was born to an aristocratic family in Stageira, Macedonia in 384 B.C. His father, Nicomachus, was the personal physician to King Amyntas of Macedon. Aristotle’s mother, Phaestis, came from an aristocratic family in Euboea, and Aristotle was trained and educated as a member of the aristocracy. Orphaned at the age of 10, he was taken under the care of a man named Proxenus. At the age of 17 (some text say 18), he moved to Athens to complete his education at Plato’s famous Academy, where he remained for nearly twenty years (first as a star student and then as a teacher) until after Plato’s death in 347 B.C.

Aristotle was arguably the brightest student in the Academy and he was groomed to replace Plato. However, Plato’s nephew Speusippus (407 – 339 B.C.) was chosen (partly because Aristotle’s ideas had diverged too far from Plato’s). Aristotle left the Academy and embarked on an educational journey to Asia Minor. While staying at the court of Hermias of Atarneus, an ex-student of Plato, he met and married Hermias’ daughter, Pythias, and together they had a daughter also called Pythias. After Hermias’ death, Aristotle was invited by Philip of Macedon to tutor to the young Alexander the Great. His wife Pythias died soon after, and Aristotle Herpyllis from his home town of Stageira, and they had a son named after Aristotle’s father, Nicomachus.

In 335 Aristotle founded his own school, the Lyceum, in Athens. Because of his practice of lecturing in the Lyceum’s walking place, or peripatos, Aristotle’s followers became known as the peripatetics, or the “walkers.”¨The Lyceum had a broader curriculum than the Academy, and a stronger emphasis on natural philosophy. Aristotle systematized and extended the limits of all the academic disciplines then known such as Biology, Psychology, Zoology, Physics, Astronomy, Ethics, Politics, Aesthetics, Metaphysics, and Logic.

The Works of Aristotle

Aristotle’s works are often classified as:

- The Organon which consisted of six treatises on logic;

- The Rhetoric which deals with his studies on persuasive speech, argumentation and debate;

- The Poetics his theory of drama and literature;

- The Physics works on natural science and the study on matter and energy;

- The De Anima his work on the characteristics of the human body and soul;

- The Metaphysics and the works on the reality of being;

- The Ethics (often called the Nicomachean Ethics or the Eudaimonian Ethics) his treatise on what is good and moral;

- The Politics which highlight his view on government and state.

Plato and Aristotle

Aristotle was a studious type, and no doubt learned a great deal from his master, but he was also of a very different temperament. Where Plato was brilliant and intuitive, Aristotle was scholarly and methodical. Nevertheless, there was an obvious mutual respect as Aristotle was the Academy’s brightest pupil. However, Plato and Aristotle differed in their opinion of the nature of universal qualities. For Plato, they reside in the higher realm of the Forms, but for Aristotle they reside here on Earth.

Aristotle was a studious type, and no doubt learned a great deal from his master, but he was also of a very different temperament. Where Plato was brilliant and intuitive, Aristotle was scholarly and methodical. Nevertheless, there was an obvious mutual respect as Aristotle was the Academy’s brightest pupil. However, Plato and Aristotle differed in their opinion of the nature of universal qualities. For Plato, they reside in the higher realm of the Forms, but for Aristotle they reside here on Earth.

In criticizing Plato’s World of Forms (Ideas), Aristotle asked:

- If Forms are essences of things, how can they exist separated from things?

- If they are the cause of things, how can they exist in a different world?

Aristotle’s later argument against the theory of Forms was more straightforward, and more directly related to his studies of the natural world. He realized that it was simply unnecessary to assume that there is a hypothetical realm of Forms, when the reality of things can already be seen here on Earth, inherent in everyday things.

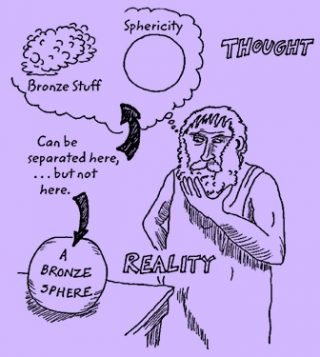

Form and Matter

Aristotle employed some of the same terminology as Plato. He said that a distinction must be drawn between form and matter, but that these two features of reality can be distinguished only in thought, not in fact. Forms are not separate entities. They are embedded in particular things. For example, all dogs share the same characteristics of being dogs, that’s why we call them dogs regardless of their breed and origin. They are in the world. A particular object, to count as an object at all, must have both form and matter. An object’s matter is what is unique to that object. Aristotle called it the object’s “thisness” but no two have the same matter. Matter is “the principle of individuation.” An object with both form and matter is what Aristotle called a substance.

Aristotle employed some of the same terminology as Plato. He said that a distinction must be drawn between form and matter, but that these two features of reality can be distinguished only in thought, not in fact. Forms are not separate entities. They are embedded in particular things. For example, all dogs share the same characteristics of being dogs, that’s why we call them dogs regardless of their breed and origin. They are in the world. A particular object, to count as an object at all, must have both form and matter. An object’s matter is what is unique to that object. Aristotle called it the object’s “thisness” but no two have the same matter. Matter is “the principle of individuation.” An object with both form and matter is what Aristotle called a substance.

Each substance contains an essence, which is roughly equivalent to its form, as in Plato’s writings; but unlike in Plato’s account, in Aristotle’s theory the essence cannot be separated from the substance in question. However, it is possible to perform the purely intellectual act of abstracting the essence from the substance and this process is called abstraction. Indeed, part of the philosopher’s job is to discover and catalog the different substances in terms of their essences and their accidents, that is in terms of those features of the substance that are essential to it, and those that are not essential.

For instance:

“To be human, one must be rational, so rationality is part of the human essence; but although every human either has hair or is bald, neither hairiness nor baldness is essential to human nature, hence, hairiness or baldness is just an accident to being human.”

Idealism and Realism

The clashing philosophical outlook of the teacher and student was not certainly new. Pre-Socratic philosophers opposed each other’s ideas too. Plato’s world of ideas (idealism) was also known as dualism while Aristotle’s world or real substances was to become known as pluralism. Aristotle’s anti-Platonic metaphysics holds that reality is composed of a plurality of substances. It is not composed of an upper tier of eternal Forms and a lower tier of matter that unsuccessfully attempts to imitate those Forms. This theory represents Aristotle’s pluralism as opposed to Plato’s dualism (a dualism that verges on idealism because, for Plato, the most “real” tier of reality is non-material and is found not in this world).

On the Concept of Change

Potentiality and Actuality

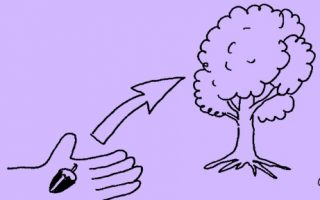

Aristotle’s pluralism attempted to solve the problem of motion and change, a problem that was unsuccessfully addressed by his predecessors. He does so by reinterpreting matter and form as potentiality and actuality and by turning these concepts into a theory of change. Any object in the world can be analyzed in terms of these categories. Aristotle’s famous example is that of an acorn.

Aristotle’s pluralism attempted to solve the problem of motion and change, a problem that was unsuccessfully addressed by his predecessors. He does so by reinterpreting matter and form as potentiality and actuality and by turning these concepts into a theory of change. Any object in the world can be analyzed in terms of these categories. Aristotle’s famous example is that of an acorn.

The acorn’s matter contains the potentiality of becoming an oak tree, which is the acorn’s actuality. The acorn is the potentiality of there being an oak tree. The oak tree is the actuality of the acorn. So, for Aristotle, form is an operating cause. Notice that a substance’s essence does not change, but its accidents do. An acorn for sure becomes an oak tree, not an acacia or narra trees.

The Four Causes

Aristotle analyzed all changes in terms of four causes.

Aristotle analyzed all changes in terms of four causes.

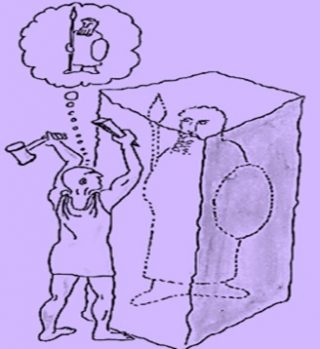

- The material cause is the stuff out of which something is made (e.g., a chunk of marble that is to become a statue).

- The formal cause is the form, or essence, of the statue, that which it strives to be. (This form exists both in the mind of the artist and potentially in the marble itself.)

- The efficient cause is the actual force that brings about the change (the sculptor’s chipping the block of stone).

- The final cause is the ultimate purpose of the object (e.g., to beautify the Parthenon).

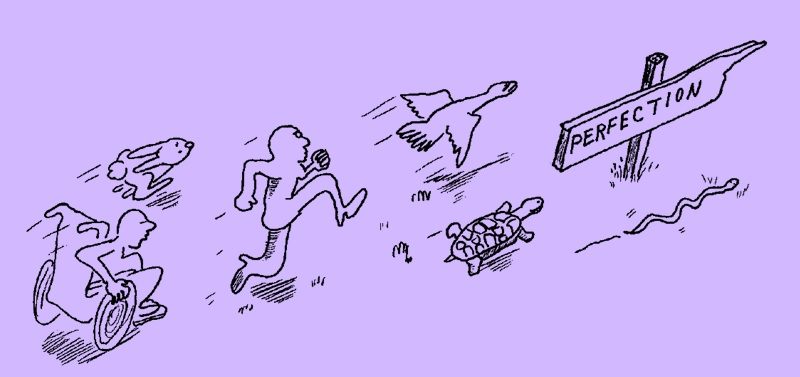

Teleological System

For Aristotle, each individual substance is a self-contained teleological (i.e., goal-oriented) system. Nature, then, is a teleological system in which each substance is striving for self-actualization and for whatever perfection is possible within the limitations allowed it by its particular essence. In Aristotle’s theory, as in Plato’s theory, everything is striving unconsciously toward the Good. Aristotle believed that for such a system to work, some concrete perfection must actually exist as the telos (or goal) toward which all things are striving.

This entity Aristotle called the Prime Mover. It serves as a kind of god in Aristotle’s metaphysics, but unlike the traditional gods of Greece and unlike the God of Western religion, the Prime Mover is almost completely non-anthropomorphic. It is the cause of the universe, not in the Judeo-Christian sense of creating it out of nothing, but in the sense of a Final Cause; everything moves toward it in the way a runner moves toward a goal. The Prime Mover is the only thing in the universe with no potentiality because, being perfect, it cannot change. It is pure actuality, which is to say, pure activity. What activity?

This entity Aristotle called the Prime Mover. It serves as a kind of god in Aristotle’s metaphysics, but unlike the traditional gods of Greece and unlike the God of Western religion, the Prime Mover is almost completely non-anthropomorphic. It is the cause of the universe, not in the Judeo-Christian sense of creating it out of nothing, but in the sense of a Final Cause; everything moves toward it in the way a runner moves toward a goal. The Prime Mover is the only thing in the universe with no potentiality because, being perfect, it cannot change. It is pure actuality, which is to say, pure activity. What activity?

The activity of pure thought. And what does it think about? Perfection! That is to say, about itself. The Prime Mover’s knowledge is immediate, complete self-consciousness.

Nichomachean Ethics

Nichomachean ethics is the other name of the moral philosophy (ethics) of Aristotle. It was named after his father/son Nichomachus. Aristotle noted that every act is performed for some purpose, which he defined as the “good” of that act. We perform an act because we find its purpose to be worthwhile. Either the totality of our acts is an infinitely circular series. If we don’t seek the goal, ours would be a meaningless life.

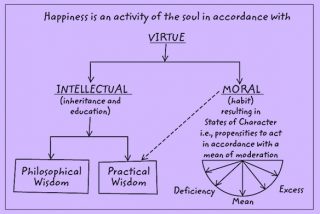

According to Aristotle, there is general verbal agreement that the end toward which all human acts are directed is Happiness (eudaimonia); Therefore, happiness is the human good because we seek happiness for its own sake, not for the sake of something else. Happiness is “an activity of the soul which is in accordance with virtue” and which “is in conformity with reason.”

The Greek word for virtue is areté which could equally be translated as “excellence.” Areté is that quality of any act, endeavor, or object that makes them successful acts, endeavors, or objects. It is, therefore, a functional excellence. For Aristotle, there are two kinds of virtue: intellectual and moral virtues. The habits that we develop result in states of character. Characters are virtuous if they result in acts that are in accordance with a golden mean of moderation. For example, when it comes to facing danger, one can act with excess, that is, show too much fear (cowardice). Or one can act deficient by showing too little fear (foolhardiness). Or one can act with moderation, and hence virtuously, by showing the right amount of fear (courage).

The Greek word for virtue is areté which could equally be translated as “excellence.” Areté is that quality of any act, endeavor, or object that makes them successful acts, endeavors, or objects. It is, therefore, a functional excellence. For Aristotle, there are two kinds of virtue: intellectual and moral virtues. The habits that we develop result in states of character. Characters are virtuous if they result in acts that are in accordance with a golden mean of moderation. For example, when it comes to facing danger, one can act with excess, that is, show too much fear (cowardice). Or one can act deficient by showing too little fear (foolhardiness). Or one can act with moderation, and hence virtuously, by showing the right amount of fear (courage).

For Aristotle, intellectual virtue can be acquired through a combination of inheritance and education. It has two forms:

- Practical wisdom – necessary to make judgments consistent with one’s understanding of the good life.

- Philosophical wisdom – is scientific, disinterested, and contemplative. It is associated with pure reason.

Philosophical wisdom is the highest virtue. The human being can be happy only by leading a contemplative life, but not a monastic one. We are not only philosophical animals but also social ones. We are engaged in a world where decisions concerning practical matters are forced upon us constantly. Happiness (hence the good life) requires excellence in both spheres.