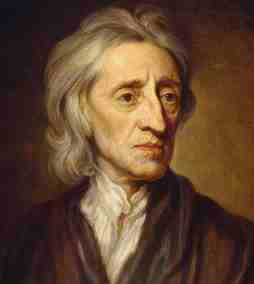

Welcome to this topic on John Locke! John Locke is the founder of British Empiricism. Along with George Berkeley and David Hume, John Locke spearheaded the empiricism philosophy of the 17th century which provided the stark challenge to the 16th century continental rationalism of Descartes, Spinoza and Leibniz. In this topic, we will examine the basic features of Lockean philosophy as he established the foundations of empiricism. A philosophy which has influenced as many as modern concepts in various fields of endeavor such as epistemology, educational psychology, political science and ethics, to name a few. So, hang on and together, let us experience the empirical lens of John Locke.

“Where is the man that has incontestable evidence of the truth of all that he holds, or of the falsehood of all he condemns, or can say that he has examined to the bottom all his own, or other men’s, opinions? The necessity of believing without knowledge, nay often upon very slight grounds, in this fleeting state of action and blindness we are in, should make us more busy and careful to inform ourselves than constrain others.” ~ John Locke

Intended learning outcome

At the time of completion of this topic, you should be able to:

- Explain the epistemological ideas of John Locke; and

- Cite specific contributions of John Locke in various fields of study.

Who is John Locke?

John Locke (1632-1704) was the son of a West of England lawyer who fought with the Parliamentarians against the King in the English Civil War. In 1646 Locke was sent to Westminster school, at that time perhaps the best school in England, and learned not only the classics but Hebrew and Arabic. From there he passed into Oxford University, where he discovered the new philosophy and the new science, becoming eventually qualified in medicine. He began to get involved in public affairs at the level of secretary and adviser. In 1667 he took up residence in the household of the Earl of Shaftesbury, leader of the parliamentary opposition to King Charles II, as his personal physician, though in fact serving him in other and more political capacities also.

He spent the four years 1675-79 in France, where he studied Descartes and came into contact with some of the greatest minds of the age. In 1681 the Earl of Shaftesbury was tried for treason, and acquitted, but fled the country out of fear for his safety, and settled in Holland. Things became dangerous for his associates in England, so in 1683 Locke too left England for Holland. It was there that he wrote the bulk of his masterpiece Essay concerning Human Understanding, though he had been working on it since 1671. It was published in 1689.

How do we learn?

What we have direct experience of, said Locke, are the contents of our own consciousness – sensory images, thoughts, feelings, memories, and so on, in enormous profusion. To these contents of consciousness, he gave the name “ideas,” regardless of whether they are intellectual, sensory, emotional, or anything else: what Locke means by an idea is simply anything that is immediately present to conscious awareness. As regards our knowledge of the external world, he insists, the raw data, the basic input, comes to us through our senses: we are increasingly in receipt of specific impressions of light or dark; red, yellow, or blue; hot or cold; rough or smooth; hard or soft, and so on and so forth; to which in the early stages of our conscious lives, we are not even able to give names. But we register them from the beginning, and remember some of them, and begin to associate some with others, until eventually we begin to form general notions and expectations about them. We start to acquire the general idea of things, objects outside ourselves from which we are receiving these impressions; and then we begin the process of learning to distinguish one thing from another we begin to discriminate, say, a furry object that is always around the place and moves about on four legs and makes a particular kind of noise: eventually we will learn to call it a dog. From beginnings such as these our minds and our memories build up ever more complex and sophisticated ideas on the ultimate basis of our sensory input, and gradually we acquire an intelligible view of the world; and we develop also the ability to think about it.

One thing Locke emphasizes is that our senses constitute the only direct interface between ourselves and the reality external to us: it is only through our senses that anything of which we can ever become aware is able to get into us from outside. We develop the capacity to do all sorts of marvelous and complicated things inside our heads with these data; but if we start performing those operations on material which does not come from our (or somebody’s) sensory input we have forfeited the mind’s only link with external reality. In that case, whatever the mind’s operations may or may not be doing, they are not connecting up with anything that exists in the external world. Of course, the mind can produce, from within its own resources, dreams and all sorts of other fictions to which nothing in the external world corresponds; and there are many circumstances in which they do that. But Locke came to the conclusion that our notions about what actually exists – and therefore our understanding of reality, of the world – must always derive ultimately from what has been experienced through the senses, or else has to be constructed out of elements that derive in the end from such experience.

This is the nub of empiricism. As usual with any philosophical doctrine, an essential part of the point lies in what it rules out. It denies, for instance, the notion (accepted by Plato) that we are born with a certain amount of knowledge of the world that we have acquired in a previous existence. Much more germane to Locke’s own time, it denied Descartes’ doctrine that, starting with nothing but the contents of our own consciousness; we can validate our conception of the external world. In fact, Locke was against the notion of innate ideas in any form: he thought there were no such things. He believed that when we are born the mind is like a blank sheet of paper (tabula rasa).

Tabula rasa

He wrote, “Let us then suppose the mind to be, as we say, white paper, void of all characters, without any ideas: How comes it to be furnished? . . . To this I answer, in one word, from experience.” So the mind at birth is a tabula rasa, a blank slate, and is informed only by “experience,” that is, by sense experience and acts of reflection. Locke built from this theory an epistemology beginning with a pair of distinctions: one between simple ideas and complex ideas and another between primary and secondary qualities.

Simple ideas originate in any one sense (though some of them, like “motion,” can derive from either the sense of sight or the sense of touch). These ideas are simple in the sense that they cannot be further broken down into yet simpler entities. (If a person does not understand the idea of “yellow,” you can’t explain it. All you can do is point to a sample and say, “yellow.”) These simple ideas are Locke’s primary data, his psychological atoms. All knowledge is in one way or another built up out of them.

Complex ideas are, for example, combinations of simple ideas. These result in our knowledge of particular things (e.g., “apple”—derived from the simple ideas “red,” “spherical,” “sweet”), comparisons (“darker than”), relations (“north of”), and abstractions (“gratitude”). Even abstractions, or general ideas, are nevertheless particular ideas that stand for collections. (This doctrine places Locke close to the theory known in the medieval world as “nominalism.” Nominalism is a philosophy claiming that the universals do not name independent forms, essences, or general similarities that truly exist in the natural world. Rather, they are mere names designating convenient categorizations of the world for pragmatic human interaction with it. (All the empiricists share with the nominalists the anti-Platonic thesis that only particulars exist.)

Locke’s distinction between primary and secondary qualities is one that he borrowed from Descartes and Galileo, who had in turn borrowed it from Democritus. Primary qualities are characteristics of external objects. These qualities really do inhere in those objects. (Extension, size, shape, and location are examples of primary qualities.) Secondary qualities are characteristics that we often attribute to external objects but that in fact exist only in the mind, yet are caused by real features of external objects. (Examples of secondary qualities are colors, sounds, and tastes.) This view of the mind has come to be known as “representative realism.” Representative realism believes that the mind represents the external world, but it does not duplicate it. Naive realism believes that the mind literally duplicates external reality.

So in Locke’s system, as in Descartes’ system, there is a real world out there and it has certain real qualities—the primary qualities. Now, these qualities—what are they qualities of? In answering this question, Locke never abandoned the basic Cartesian metaphysics of substance. A real quality must be a quality of a real thing, and real things are substances. (Once again, everything in the world is either a substance or a characteristic of a substance.) Well then, what is the status of this pivotal idea of “substance” in Locke’s theory? Recall that Descartes had claimed that one cannot derive the idea of substance from observation precisely because perception can only generate doubtful qualities. For this very reason, it was necessary to posit the idea of substance as an innate idea. But Locke was committed to the rejection of innate ideas and to the claim that all knowledge comes in through the senses.

Contributions of John Locke

John Locke is a thinker of the front rank in two different areas, Epistemology which is the study of the theory of knowledge and political philosophy. In the former he launched what many to this day regard as its most important project, namely an enquiry into what are the limits to what is intelligible to humans. People before him had tended to assume that the limits to what could be known were set by the limits to what there is – that in principle, at least, we could go on finding out more and more about reality until there was nothing left to find out. There had always been philosophers who understood that limits of a different sort might also exist, namely limits to what it is possible for humans to apprehend, in which case there might be aspects of reality which humans can never know or understand. This realization was almost universal among medieval philosophers. But Locke secularized it, and then took it an important stage further. If, he thought, we could analyze our own mental faculties and find out what they are capable, and what they are not capable, of dealing with, we should have discovered the limits of what is knowable by us, regardless of what happens to exist externally to ourselves. No matter how much (or little) exists over and above what is apprehensible to us; it will have no way of getting through to us.

Mankind began, says Locke, in a state of nature. As a creature made by God in His own image man was not, even in a state of nature, a jungle beast, for God had given him reason and conscience. So Locke’s view of the state of nature is very different from Hobbes. Even so, the absence of any such things as government or civil order is so greatly to the detriment of human beings that, John Locke believed, individuals came together voluntarily to create society. As with Hobbes, the social contract is seen as being not between government and the governed but between free men. Unlike Hobbes, however, Locke sees the governed as retaining their individual rights even after government has been set up. Sovereignty ultimately remains with the people. The securing of their rights – the protection of the life, liberty, and property of all – is the sole legitimate purpose of government. If a government begins to abuse those rights (i.e. becomes tyrannical) or ceases to defend them effectively (i.e. becomes ineffectual) the governed retain a moral right – after seeking redress through normal procedures and failing to obtain it – to overthrow the government and replace it with one that does the job properly. This explains, incidentally, Locke’s role in the Glorious Revolution of 1688.

This is why John Locke called his masterpiece Essay concerning Human Understanding and why, at the very beginning of the book, he says he regarded it as “necessary to examine our own abilities, and see what objects our understandings were, or were not, fitted to deal with.” In doing this he launched an enquiry which was taken up after him by some of the outstanding figures in philosophy – Hume and Kant in the 18th century, Schopenhauer in the 19th; then Russell, Wittgenstein and Popper in the 20th. Each of these individuals felt a sense of special indebtedness to others who preceded him in this line of succession, a linked chain that can be said now to constitute a tradition.

References

- Dorling Kindersley. (2011). The Philosophy Book. New York: DK Publishing.

- Stumpf, Samuel Enoch. (2008). From Socrates to Sartre and Beyond. New York: McGraw Hill Publishing.

- Palmer, Donald.(2006). Looking at philosophy:The unbearable heaviness of philosophy made lighter 4th Edition. New York: McGraw Hill Companies.

- Ramos, Christine Camela. (2004). Introduction to Philosophy. Manila: Rex Bookstore.

- Gaarder, Jostein. (2004). Sophie’s World. Great Britain: Phoenix House.

- http://www.plato.standford.edu