Welcome to this topic focusing on the philosophy of Soren Kierkegaard! The Dane Søren Kierkegaard (1813–1855) is a very fascinating philosopher. Kierkegaard, who is generally recognized today as the father of existentialism, thought of himself primarily as a religious author and an antiphilosopher. In truth, he was not opposed to philosophy as such but to Hegel’s philosophy. Nevertheless, like the rest of his generation, Kierkegaard fell more under Hegel’s spell than he would have liked to admit.

Welcome to this topic focusing on the philosophy of Soren Kierkegaard! The Dane Søren Kierkegaard (1813–1855) is a very fascinating philosopher. Kierkegaard, who is generally recognized today as the father of existentialism, thought of himself primarily as a religious author and an antiphilosopher. In truth, he was not opposed to philosophy as such but to Hegel’s philosophy. Nevertheless, like the rest of his generation, Kierkegaard fell more under Hegel’s spell than he would have liked to admit.

“Life can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards.” ~ Soren Kierkegaard

Who is Soren Kierkegaard?

Søren Kierkegaard was born in Copenhagen in 1813, in what became known as the Danish Golden Age of culture. His father, a wealthy tradesman, was both pious and melancholic, and his son inherited these traits, which were to greatly influence his philosophy. Kierkegaard studied theology at the University of Copenhagen, but attended lectures in philosophy. When he came into a sizeable inheritance, he decided to devote his life to philosophy. In 1837 he met and fell in love with Regine Olsen, and three years later they became engaged, but Kierkegaard broke off the engagement the following year, saying that his melancholy made him unsuitable for married life. Though he never lost his faith in God, he continually criticized the Danish national church for hypocrisy. In 1855 he fell unconscious in the street, and died just over a month later.

Key philosophical works

- 1843 Either/Or

- 1843 Fear and Trembling

- 1844 The Concept of Anxiety

- 1847 Works of Love

The Philosophy of Soren Kierkegaard

Søren Kierkegaard’s philosophy developed in reaction to the German idealist thinking that dominated continental Europe in the mid-19th century, particularly that of Georg Hegel. Kierkegaard wanted to refute Hegel’s idea of a complete philosophical system, which defined humankind as part of an inevitable historical development, by arguing for a more subjective approach. He wants to examine what “it means to be a human being”, not as part of some great philosophical system, but as a self-determining individual.

Kierkegaard’s philosophy, as opposed to the abstractions of Hegelian philosophy, would return us to the concreteness of existence. But he was not so much interested in the concreteness of existence of things in the world as he was in the concreteness of individual human existence. René Descartes had been right to begin philosophy with the self (“I think, therefore I am”), but he had been wrong, as was Hegel after him, to equate the self with thought. “To think is one thing, to exist is another,” said Kierkegaard. I can think and say many things about myself—“I am a teacher, I am a man, I am a Filipino, I am in love, I prefer vanilla over chocolate.” Yet, when I am done talking and thinking about myself, there is one thing remaining that cannot be thought—my existence, which is a “surd” (an irrational residue). I cannot think it; rather, I must live it.

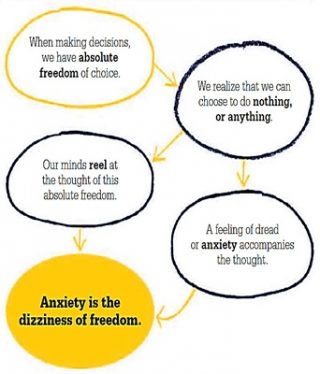

Kierkegaard believes that our lives are determined by our actions, which are themselves determined by our choices, so how we make those choices is critical to our lives. Like Hegel, he sees moral decisions as a choice between the hedonistic (self-gratifying) and the ethical. But where Hegel thought this choice was largely determined by the historical and environmental conditions of our times, Kierkegaard believes that moral choices are absolutely free, and above all subjective. It is our will alone that determines our judgement, he says. However, far from being a reason for happiness, this complete freedom of choice provokes in us a feeling of anxiety or dread.

Kierkegaard explains this feeling in his book, The Concept of Anxiety. As an example, he asks us to consider a man standing on a cliff or tall building. If this man looks over the edge, he experiences two different kinds of fear: the fear of falling, and fear brought on by the impulse to throw himself off the edge. This second type of fear, or anxiety, arises from the realization that he has absolute freedom to choose whether to jump or not, and this fear is as dizzying as his vertigo. Kierkegaard suggests that we experience the same anxiety in all our moral choices, when we realize that we have the freedom to make even the most terrifying decisions. He describes this anxiety as “the dizziness of freedom”, and goes on to explain that although it induces despair, it can also shake us from our unthinking responses by making us more aware of the available choices. In this way it increases our self-awareness and sense of personal responsibility.

Kierkegaard explains this feeling in his book, The Concept of Anxiety. As an example, he asks us to consider a man standing on a cliff or tall building. If this man looks over the edge, he experiences two different kinds of fear: the fear of falling, and fear brought on by the impulse to throw himself off the edge. This second type of fear, or anxiety, arises from the realization that he has absolute freedom to choose whether to jump or not, and this fear is as dizzying as his vertigo. Kierkegaard suggests that we experience the same anxiety in all our moral choices, when we realize that we have the freedom to make even the most terrifying decisions. He describes this anxiety as “the dizziness of freedom”, and goes on to explain that although it induces despair, it can also shake us from our unthinking responses by making us more aware of the available choices. In this way it increases our self-awareness and sense of personal responsibility.

The Father of Existentialism

Soren Kierkegaard’s ideas were largely rejected by his contemporaries, but proved highly influential to later generations. His insistence on the importance and freedom of our choices, and our continual search for meaning and purpose, was to provide the framework for existentialism. This philosophy, developed by Friedrich Nietzsche and Martin Heidegger, was later fully defined by Jean-Paul Sartre. It explores the ways in which we can live meaningfully in a godless universe, where every act is a choice, except the act of our own birth. Unlike these later thinkers, Kierkegaard did not abandon his faith in God, but he was the first to acknowledge the realization of self-consciousness and the “dizziness” or fear of absolute freedom.

Works Cited

- Stumpf, Samuel Enoch. (2008). From Socrates to Sartre. New York: McGraw Hill Publishing.

- Palmer, Donald. (2006). Looking at Philosophy: The unbearable heaviness of philosophy made ligther, 4th Edition. New York: McGraw Hill Higher Education.

- Ramos, Christine Camela. (2004). Introduction to Philosophy. Manila: Rex Bookstore.

- Gaarder, Jostein. (2004). Sophie’s World. Great Britain: Phoenix House.

- http://www.plato.standford.edu

- http://www.philosophybasic.com